In the first part, Veles, in Macedonia, revealed itself as a city of slopes and pauses, a place read by walking and misreading, by looking at houses instead of monuments. This second text doesn’t restart the journey—it continues it, with a heavier body and a sharper eye. Days two and three move deeper into the city’s layers: across bridges and under them, through graffiti, scaffolding, rust, and conversations that begin with “What are you photographing?” What follows is not a sequel but a descent and return—an urban archaeology that tests the same method again, this time where the city resists, contradicts, and quietly answers back.

A new day—new challenges (if you don’t know who “the old day” is, click here!). I wake up with a clogged nose, a throat like sandpaper, a head banging like a railway barrier, and a fever (no idea how high—I don’t even own a thermometer). Five or six attempts to get up (open eyes, then ctrl+alt+del). Success on the seventh. The mission continues. Veles is waiting. Hills upon hills, journalistic troubles large!

“Malo Movče,” the quay, and kayaks

The iron pedestrian bridge looks at me like a scene from a familiar film. Locals call it “The Old Bridge,” “Malo Movče”; it’s not the Railway Bridge (that’s another one—I’ll get to it later). First built in 1863 (wooden back then). It stirs memories of Sarajevo, my birthplace. Bridges as stitches of history.

I stop by the tracks, behind the shopping center with the four markets (see text 1). How do I cross? Out of the corner of my eye I spot people popping out like moles from some hole. There it is—the little tunnel under the rails, a secret passage to the other side of the city.

And there—faded Draš (a graffiti legend of the Skopje scene). Joy (like running into an old friend in a foreign city). Inside the tunnel, graffiti that once had form and color, now crossed out and trampled by time. Outside, in front of the bridge—a wooden-iron statue of some male–female duality (Google is no help!).

Under the bridge—the quay that abruptly ends on both sides; a retaining wall half new, half story (I google—it’s been under reconstruction for years…). Beautiful, large old houses along the quay. Some renovated, some decaying. Suddenly: two kayakers in the water. I wave; they lift their paddles.

I climb onto the bridge. I frame a shot with the Clock Tower in the background, construction machines in the foreground—past and future in the same scene. It hits me! I pull stickers from my backpack. I slap one on, made after a graffiti by Hrom (an important graffiti figure, owner of the first Skopje graffiti shop, since 2010). His graffiti near the “Kole Nedelkovski” elementary school was replaced by a commissioned amateur mural of Blagoja Drnkov—far weaker. The sticker is my mini-revenge on oblivion.

The other side: anarchy on the quay (and a lovely contradiction)

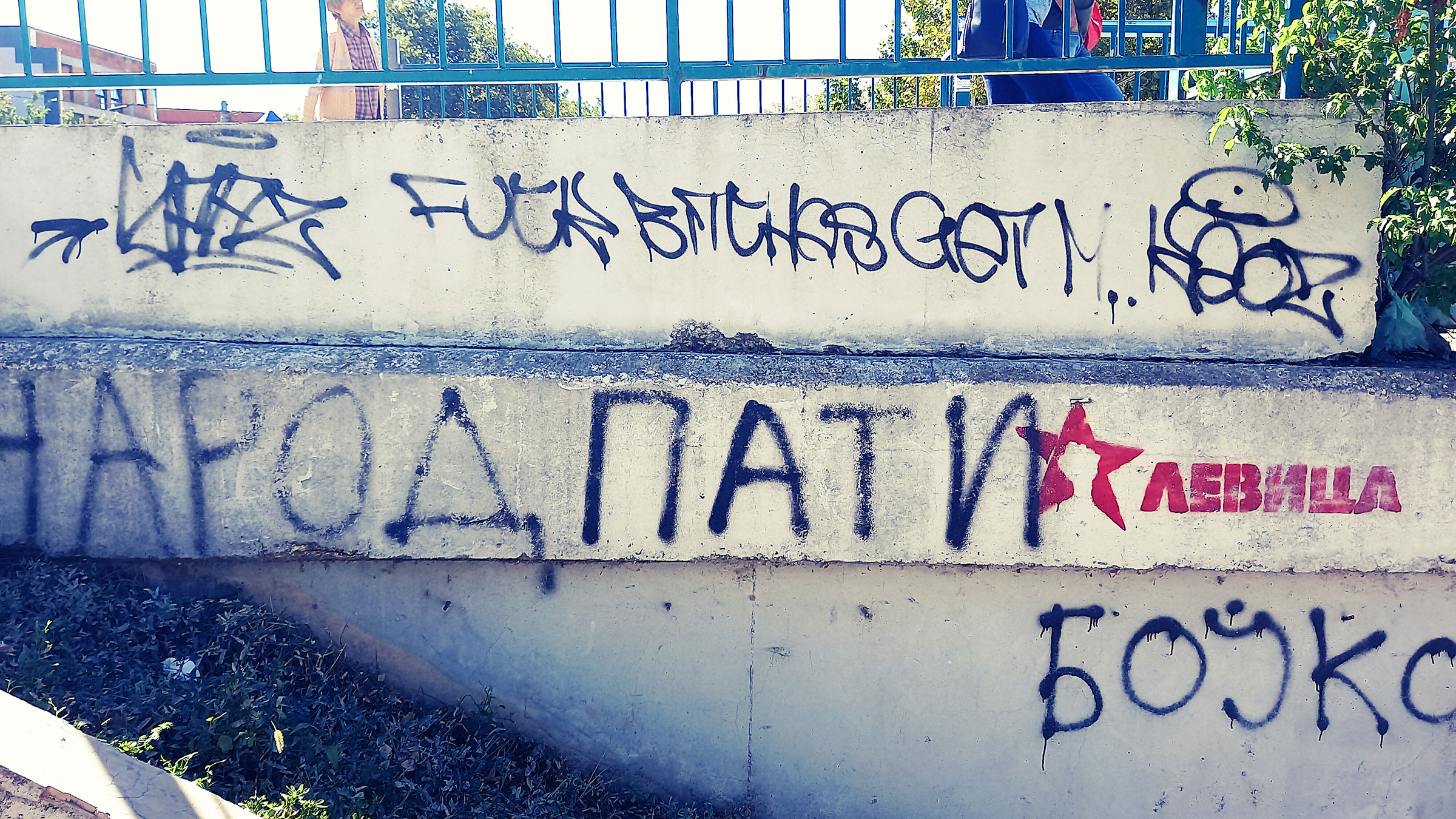

From the bridge I spot throw-ups on the opposite side of the quay—I run there. Under the bridge—trash, chaos, political graffiti. For the first time in Veles I see “Skopje scenes.” The capital greets tourists right at the train-bus station with garbage (in Veles you have to make a bit of effort to find it). I photograph everything. There’s quite a bit of graffiti. As long as the wall—and it’s not long. For someone used to the kilometer-long retaining walls of Skopje’s quay, it’s modest.

Graffiti on the left bank of the Vardar

Above the quay—more graffiti, mostly names and one “H+C Fack the Police.” Some young punk wrote the spelling mistake with full intention: message + youth = rebellion. And right there, the modernist monument to the Gemidzhii: “We spend ourselves for Macedonia” (how deeply that lives in me!). Two anarchist echoes—one sprayed, the other forged in metal.

Market day: another side of the city

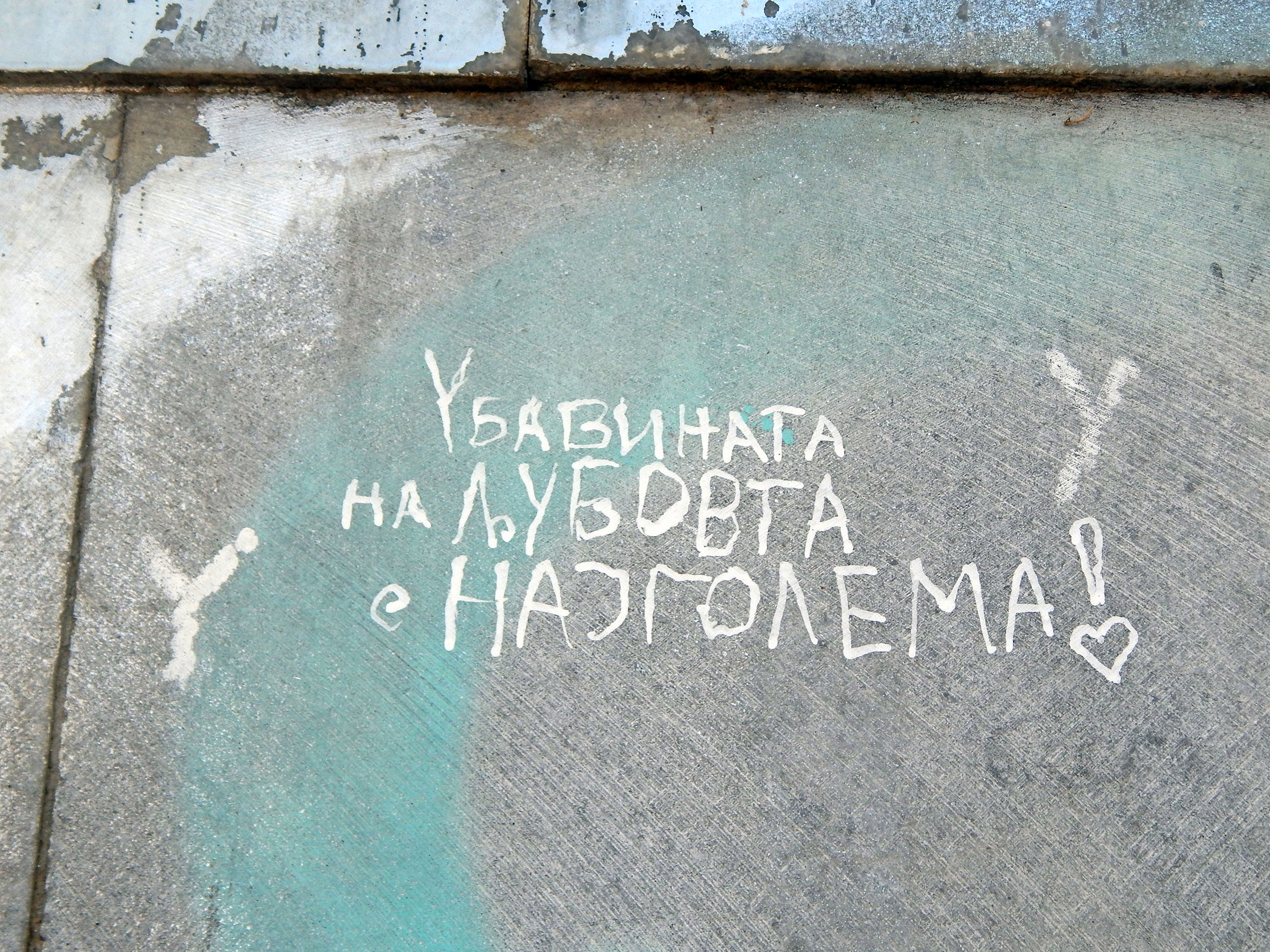

A step away from the bridge, the atmosphere switches genres like a movie. The other side—the center between the City Clock, the “Voivode on a Horse,” Kočo Racin’s monument, the church, etc.—overflows with “Skopje scenes” (insert scenes from any new-capitalist city). This side feels more authentic and vivid—street market, greengrocers, tin “butki” (Skopje in the last century), signs in old typography, old shops no longer working. Behind one stall—an enormous love graffiti; reality and romance. Balkan math.

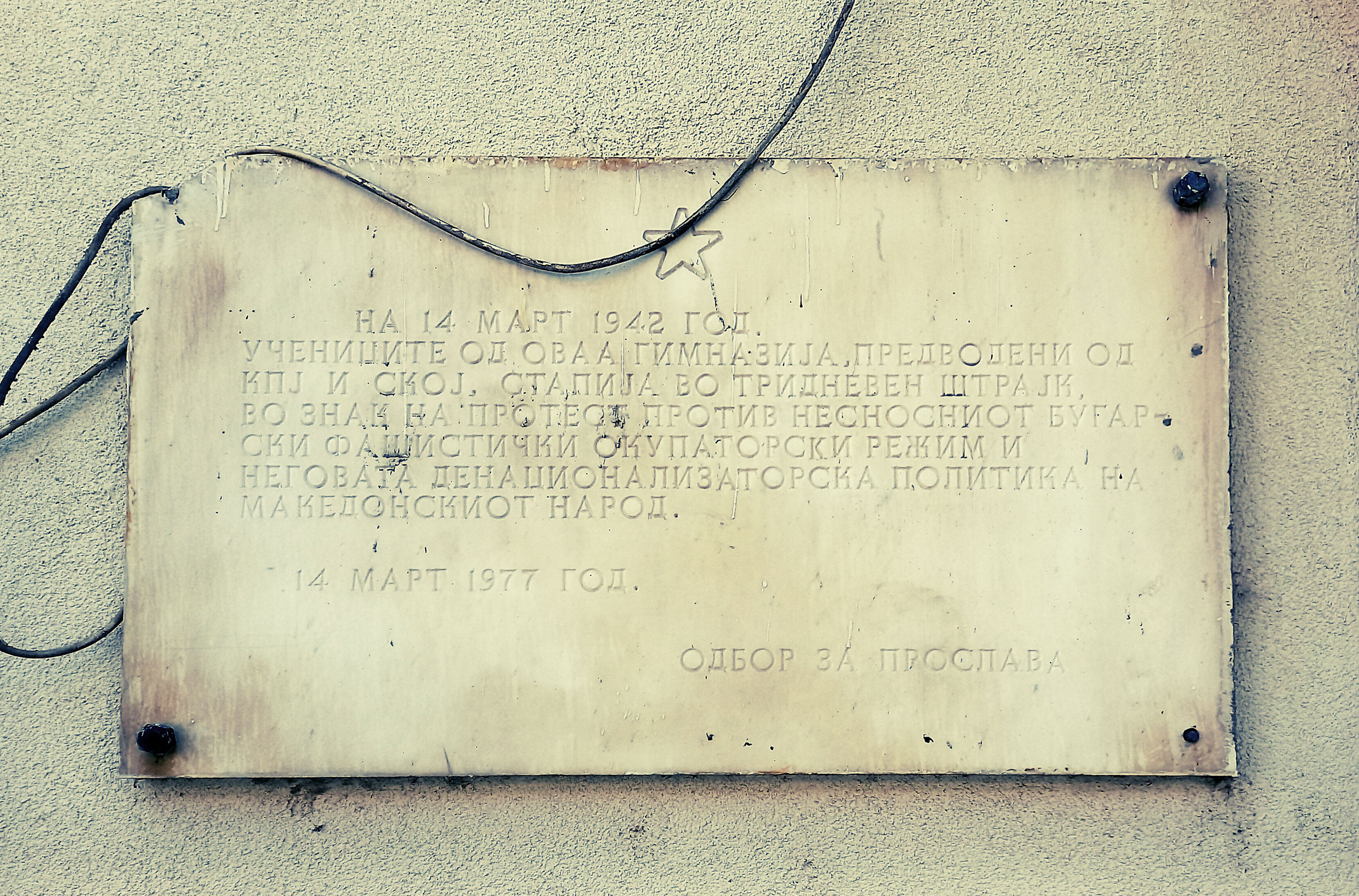

I run into the “Panko Brašnarov” elementary school: a plaque about the students’ strike in 1942 against the Bulgarian occupier. I photograph carefully, so I don’t catch a kid by mistake. A curious boy breathes down my neck:

—“What are you doing?”

—“Taking photos.”

—“Of what?”

—“Buildings, houses, streets…”

He doesn’t get it; a friend calls him—shmirgla—he’s gone.

Сцени од улицата, пазарот, дуќаните, училиштата…

The Alikara/Apasiev House: a bey’s shadow, state scaffolding

I climb the alleys (Veles neighborhood? Maybe.) Old town houses under restoration (joy!), others fallen or falling (sadness!). Some “restored” with PVC doors and windows, others bare blocks—today’s materials are often allergic to yesterday’s spirit (if only it were the other way around!).

A house with a sign “Caution—construction works.” I photograph it from every angle. Later, in conversation with Natasha A. (from Blen.mk), I learn I photographed the house of Apasiev, leader of the Left party, originally from Veles. (Google helps: mid-19th century, a bey’s house, later bought by the gardener Alikara, then the Apasievi. The state has been “restoring” it for years. Scaffolding—yes. Progress—no.) Nearby—a gorgeous house on “Jovan Naumov Alabakot” Street from 1868, vegetal ornaments on the cornices. In Italy it would be flooded with selfie sticks like reeds on a lake. Here—it’s just me, a voyeur of other people’s houses, doors, windows, and porches, intersected by (sometimes curious, often sharp) looks from residents.

“What are you photographing?”: small clashes, big truths

I head deeper into the hills and narrow lanes. I get lost. With every turn—another interesting structure. Some houses dying, others long gone, only rubble as witness to former life. I photograph one. A woman comes out:

—“What are you photographing?” Her tone is different from the child’s. His was curious. Hers is hostile.

—“Old houses, windows, doors…”

—“That’s a shed! What’s interesting there?”

—“I’ll delete the photo if it bothers you.” She points uphill: “Photograph that one—the ruined one.”

—“I already did.” She continues: “They moved to Skopje and left it like that. Now this part will collapse and bring ours down too.”

—“A shame. In Skopje few such houses remain—what the earthquake didn’t destroy, urbanization did.” She looks at me seriously, then apologizes: “Sorry I spoke like that.”

—“It’s your property, your right,” I say and head back to the main road.

Doors, windows, signs…

The Railway Bridge, rust, and a children’s playground

I’m spent. The virus collects its tax. A Lukoil gas station above me, and higher—the mural at the entrance (I promised myself I’d return with a camera, but that’s for another day). I spot a massive iron bridge twisting like a snake to the other side—the Railway Bridge (103 years old, says Google).

The bridge sits behind an auto repair shop. Inside—three mechanics. Two sit staring at the ground. One stands and looks at me. Behind the shop an enormous rusted structure reveals itself: industrial poetry in full grandeur. A sign: “Movement on the railway bridge prohibited.” I stick a few stickers on the bridge (a micro-transfer of Skopje’s spirit—does Veles need it, and who gave me the right!?). Under the bridge—a modern playground, path, equipment. Bravo, Veles—when there’s will, there’s a way.

Back to the Center, right by the Veles maples. I stick a few more stickers. On the sign before the rail underpass—one for home, one for here. Will anyone notice? Did I bring a piece of my city here?

Stickers across Veles

“Strada Café” and the Veles philosophy of “go downhill”

I grab a sandwich and collapse onto the bed. Eyes closed—five minutes, but my brain wanders. Did I miss the house of Jordan Hadži-Konstantinov Džinot on the left bank of the Vardar? I jump up—the mission isn’t over.

13:00, hot macchiato at Strada Café. I have a few “workstations” in Skopje cafés; in Veles this is it. I sit to pour notes into stories.

I message Natasha for tips on interesting locations. Should I break the methodology “get lost in the city”?

“In Veles you can’t get lost. You just go downhill. That’s a known Veles saying.”

Does my method collapse? Still—until you find the path (down), you can surely get lost up. The more you chase the peak, the more you realize where the root is (am I justifying?). That’s exactly what I did on the right side, and now on the left.

Balkan cities are strange. Rivers split them (Skopje, Struga, Veles…) into this side and that. Is that too simple? On both sides there’s always a mix: languages, foods, customs—turli-tava (La Macedonia!). Natasha gives me a few recommendations; I don’t have time to map them. It’s the last day of my blitz visit—I hope the path will take me there spontaneously.

Back over “Malo Movče”: catacombs, anarchy, and the graffiti “Dad, I love you”

I descend to the underpass, this time beneath the vehicle bridge (the New Bridge—not the old one as Wikipedia claims!). Catacombs worthy of post-apocalyptic horror. I barely squeeze through. Graffiti. Again “F*ck the Police”—Veles has an anarchy vibe in surplus (I start to understand Apasiev; though I don’t like his nationalist movie). And immediately—a rebuttal. A soft little heart reads: “Dad, I love you”—from Kiki. The first such graffiti I’ve encountered in my graffiti marathons. I remember my daughter when she was little. Stand. Breathe. Smile. On an iron gate—a cat graffiti; I photograph it to move on, legs cemented by feelings.

Across the Old Bridge, straight uphill, a neighborhood reminiscent of Karpoš; a substation with kids’/pop icons: Pokémon, Mickey, Bart, “Boom,” “Cool,” “Never,” “Limits,” signed “Gins.”

Graffiti

I head down toward the bus station and the New Bridge—a graffiti reads: “The past cannot be changed, the future is yet in your power” (signed: Artivisti—nice surprise). The road and greenery leading from the station are tidy. Bravo, Veles. Ugh, Skopje.

15:30—empty streets, closed shops, not a soul! I climb again to the ornate house on “Jovan Naumov Alabakot” and get lost among the hills once more. For me, Veles is a map that draws itself.

“The neighborhoods of Veles” as a unit of measure

“Veles is a concept of neighborhoods to me,” Natasha writes. “Each has a spirit. I grew up on the left side—I rule it. That’s where the longest street is, Vera Ciriviri. The Apasiev house is there. If you follow the stream upstream, you reach Sabotna Voda.”

I float my idea of Urban Downhill Biking through the alleys—if it works in Rio’s favelas, why not Veles? Natasha disagrees: “Madmen!” Me, a child of the ’80s and BMX, I defend it. She finishes: “These streets were made for two donkeys to pass.” That’s it.

Hills for donkeys, not people?

I squeeze between two houses so close I touch both with outstretched arms. A slope over 45 degrees. Above me—stairs, looks like the end of the world. An old man sits in a garage:

—“Is it a street up there or private property?”

—“Who are you looking for?”

—“No one, just walking.”

—“Ah… it’s nice to walk…” The old man launches into a life lesson: veins filming, disc hernia, 20,000 denars at private clinics in Skopje. He can barely move and has no clear diagnosis.

—“There are no doctors anywhere anymore,” we conclude, along with “May illness not catch you.”

A bit lower—graffiti of the Bulls, Pistons, Nuggets, Bucks (I send a photo to my son immediately!); a mini shop with Yugoslav charm (from when small Macedonian towns were alive). Risto Najdov Šajkata Street—the city in my palm, low below me. A house with a huge veranda on the porch looks at me from above.

More details from houses and steep alleys

Kosturnica: a mini-Makedonium, a mini-moon

I decide to be a “tourist” for a moment: I’ll go to Kosturnica (Natasha: “Go at sunset. And you can climb it.”). But apparently you can’t reach it through the neighborhoods. Fatigue peaks, the virus wrings me like a rag. Water on me; gunpowder in my throat.

I count: 147 steps by the Okta gas station (a mini-dump on the right—the first I see in Veles; in Skopje I’d have seen dozens by now), then 187 steps to Kosturnica. “One-sixty-something,” Natasha said—we’re close.

Kosturnica is like a mini-Makedonium in Kruševo. I climb it—the real stage is there: a panorama of the city in the palm of my hand. I feel like the Little Prince on his own asteroid. Behind the structure—a child’s drawing by a little girl. I imagine Natasha as a child.

Kosturnica

I don’t go inside: after all that hiking in the heat I probably smell like a mountain goat, and I don’t want to be a “classic tourist.” I leave Lazevski’s mosaics for another time. That drawing behind Kosturnica is my Lazevski.

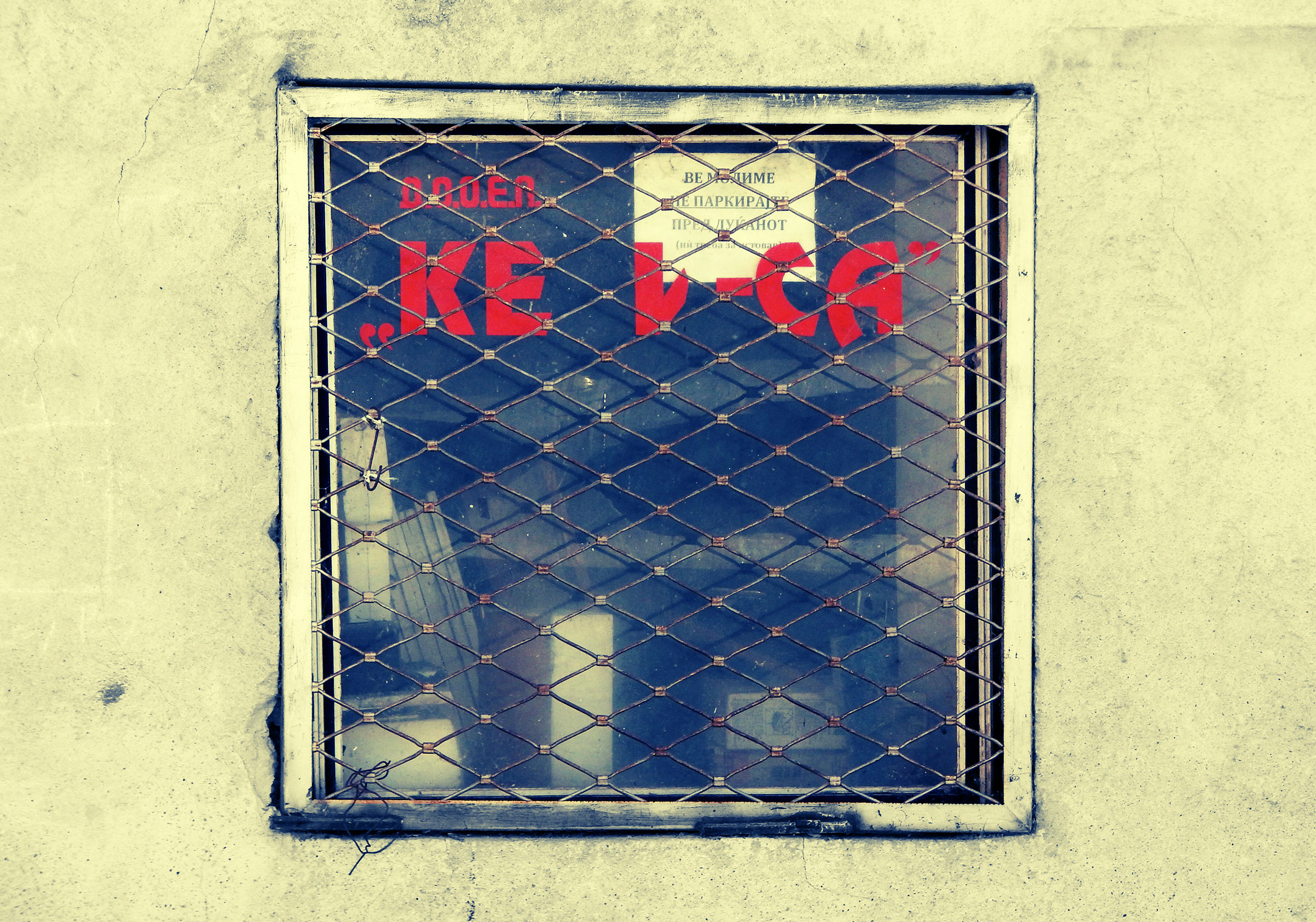

“Vulkanizer Jovica”: typography with a shadow

I head down to the main street and get hit by a sign: “Vulkanizer Jovica.” Old-school font, a shadow dancing on the inner wall—light, contrast, letters, photographic joy.

—“What are you photographing?” I hear it for the third time today. Each time with a different tone. This time the strongest. I turn—a man on a bench, frowning. The owner, I realize immediately.

—“It’s a bit complicated to explain.” He stands and approaches, hostile: “Explain then.”

—“Well, see how the sun hits the letters and casts a shadow on the wall?” He looks, puzzled. “It’s interesting. And the letters are good. Font, shadows—that.”

—“Uh-huh… and?” Not convinced, I add: “Well—art photography.”

—“Uh-huh. I’m the owner, that’s why I asked. Where are you from?”

—“Skopje. Walking around, photographing old houses and shops.”

—“Go up there—there are old Turkish and Gypsy houses.”

—“I was there; I’ll go again… The sign is interesting. How old is this place?”

—“Ah, a hundred years. But I’ll change the sign.”

—“Don’t—it’s authentic,” I say. He replies: “I have to—the glass is broken.”

—“At least I immortalized it.” A smile. We shake hands.

On the way back I think of the places I didn’t visit on Natasha’s recommendation: the “Black Mosque,” the alley from the Vlach “St. Mary” to “St. Spas,” the Vardar island—“Ada Jani Taš”… Maybe tomorrow before leaving. But my body—total shutdown. I eat, fall asleep. Evening walk—cancelled. One last thought before sleep: Veles has old buildings because it wasn’t flattened by an earthquake like Skopje. (Google corrects me: there were two big ones—1405 and 1406.) Still—history (natural forces?) sometimes spare cities before they’re fully built, so there’s something left to see (and write about!).

Day 3: departure with Racin in mind

I give in to the pressure of imaginary readers and go to Kočo Racin’s house. On the way I recognize the gate with number 13 and the fountain—I’ve already documented them. Kočo Racin Street No. 31. I arrive and realize: I photographed it already; I just missed the ivy-covered sign “Poetry Alley.” This is how important houses should be restored. A parallel Veles where architecture would be an equal to Ohrid (without the lake, but with hills).

Details from Kočo Racin’s memorial house

On the gate it says: “Working hours: Tuesday and Friday 9–15. Announced visits—any time.” My day is “ruined”! Kids around me on phones; one plays music, another says “That’s not Snoop Dogg!” Then Serbian sketches with crude humor.

On the edge of the house—a terrace decorated with jars; on the other side—a modern metal terrace. A contrast that hurts, but that’s our reality of “renovation.” Some houses restored “traditionally,” others modernized, rebuilt with blocks. The streets are so narrow, houses so close that if you rotate the photo—it becomes an Escher labyrinth that makes you dizzy. And that feels like the perfect metaphor for Veles.

I descend steep stairs, construction sites around me, emerge opposite the Commercial Bank on the main street in the Center, at the four-market shopping block. A baroque house from the 1920s—overloaded with AC units and ads; PVC windows replaced the old ones. In the middle—a window like an eye, above it a flower, ornaments by the doors. To the right—an old sign: “Watchmaker Zografski Spiro Nikola,” below it “Goldsmith-Jeweler N. Zografski.” A craftsman dynasty! The savings bank next to them slapped a two-by-one-meter sign on the façade, like patching band-aids. A shame.

Urbanism and renaissance!

The building next to them—Europe House (with that “signboard cacophony” from another day), formerly the Independent Workers’ Party headquarters in the 1950s. A bit further—a building with Skopje-1950s vibes; behind it, the 1928 baroque I caught yesterday.

Final frames: stickers, typography, “turbo-folk,” and a tractor

I keep sticking stickers, as if to spark an independent scene (or at least a treasure hunt for the curious). Finally I stumble on an interesting local sticker that doesn’t advertise a dentist: “Art Generator.” I rejoice like a child!

Again I fail to photograph the mural in the Center (maple shadows and sun create too harsh a contrast). But on the side wall of the Public Revenue Office (where the SDSM Veles office is too), next to the Court—a curiosity: “I left her because of turbo-folk.” Social realism as graffiti.

An old woman stops me, asks for some change; I pull my wallet from the overstuffed backpack (I’m only missing the priest’s hat!). “Give more—it’s a holiday,” she says. “Which one?”—“Tomorrow is Lesser Dormition.” I didn’t know. I give her a metal fifty (is that “more” these days?).

Near the roundabout with the “Voivode on a Horse,” another bitcoin sign next to an exchange office. I want a frame with the sign in front, the horse behind—modern meets traditional. It doesn’t work. Too many traffic signs—and a tractor enters the frame, as if loading the horse onto a trailer. There’s your symbol: Balkan montage.

At the car, getting ready to leave, behind the four-market block—a graffiti “Prcorek.” Let it be the final stamp in the passport of this tour (Natasha’s recommendation).

P.S. Before leaving, at Strada Café, I run into friends from Skopje, originally from Veles. I tell them about my walk, praise the hills, old façades, cleanliness. They shake their heads in disagreement. “That’s how it seems to you—you’re a tourist. It’s not like that for us.”

Maybe it’s a Macedonian curse not to love the city you’re from. I don’t love Skopje (and I do at the same time—it’s complicated).

“St. Cyril Church? Veles kebabs?” they ask. I missed the two most important things. Surely many more. Next time!

What did I learn on Days 2 & 3?

Veles has an echo of a socialist-anarchist past, administrative cacophony, old houses waiting patiently, others decaying without an audience, and signs worthy of a museum. It has Malo Movče and the New Bridge, kayakers on the Vardar, a rusty Railway Bridge (Uncle Nace is missing!) and a modern park, Kosturnica as a micro-Makedonium, and typographic gems scattered across little shops with socialist or old-town charm. It has people who ask “what are you photographing?” and people who say “send it to the Municipality—it’s a shame,” grandmothers who know which holiday it is, kids who listen to Snoop Dogg and Serbian sketches, tractors that kidnap statues, and stickers no one may notice—but that will stay there for some future “urban archaeologist.”

If the first day showed me Veles as a hill-city, the second (and third) proved it’s also a layered city: history and improvisation with hope. (Aren’t all our cities like that?) The “get lost” method holds—only in Veles you must first get lost going up, to then find yourself going down. And when you reach the bottom—you’ll want to go up again. That’s the city’s cycle. A hill for extreme sports. Gates for džindžuđinja. And a large, quiet stage—still waiting to be lit.

Read the first part of the text.

This article was originally published in Macedonian.