I set off for Veles, Macedonia. Reality check: apart from superficial bits, I know nothing! The clock tower, the ossuary, Kočo Racin—sure; but the mental map—blank. I don’t know the myths, legends, people, neighborhoods, streets. And that’s exactly how I want it: no prior knowledge, no expectations. To get lost in alleys and lanes. And to find graffiti—of course!

First impressions at the city entrance. A small digression on murals

At the entrance toward East Veles (of course East—my fate; more on that another time), by the roundabout on the so-called “Štipsko Džade” (part of the historic road linking Veles with the eastern parts of Macedonia) I’m greeted by the “Veles” mural. The style is clearly Davor Keškec’s—the Macedonian Lichtenstein (note to self: is Davor “Brk”?). Google winks: yes, the “largest mural in the country”—220 square meters, 86 meters long, 2.5 meters high. Instantly my mind flashes to the 4,100 m² mural on Dževahir Mall, or the 330-meter graffiti along the Vardar embankment signed by MZT. Is that a mural?

Matej Bogdanovski, author of books on graffiti, taught me in the early days of the Graffiti.mk group: mural—everything legal; graffiti—everything illegal. Then the artist Mile Ničevski toppled that neat order in the graffiti universe.

“So, the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo (50 meters up!), the frescoes by Mihajlo and Eustihije… or Banksy’s stencils (lower down)… and this supporter ‘graffito’ (for a third-league club, obviously drawn i.e. written by a sixth-grader :))) half a meter off the ground (!) with a cheap tin can and a brush—you call all of them by the same name? Do you know what it’s like to paint above 3–4 meters? If you fall, it’s not just a broken arm… Plus months of prep, it’s public space…”

I pulled out my camera and immediately—battery Aziz! There’s a Makpetrol across the way. A girl with long blonde hair, plumped lips and a full religious-motif sleeve—Michelangelo fresco on skin, shaded by a master—points me, disinterestedly, to where the batteries are. No big ones, only small. She’s nervously finishing her shift, chatting with someone; another employee tells me they don’t have “triple-A.” I walk out. The blonde gets into a car with another blonde—same mold, same sleeve. (Later I’ll confirm it elsewhere: the youth in Veles really like this look.)

I photograph the mural with my phone. An old man on a tractor (a common sight in Veles) honks and waves. I wave back.

The center of Veles as an opening film shot

Back in the car, I enter the city. Lodging: quickly found, right in the center, a hundred meters from the clock tower. I drop my backpack and head out to catch the city’s pulse. I have a rule: I can spot a good film in the first few seconds. Same goes for cities.

A game of rapid associations

Question: What is Veles today? Three, two, one!

Answer: Constant car bustle. Young people in cafés, elders on the street. Betting shop—pharmacy—café—bank—sandwich shop—store (groceries, clothes…)—those are the Lego bricks along the main street; shuffle them in random order.

I’m lodged in a newly concocted, almost Escher-esque shopping center that defies gravity. Suddenly in front of me: KAM, Kiper, Ramstor, Dim Market, Žito Market—an entire economy in 20 meters. KAM is the motherlode—batteries, and the adventure can begin.

Sculptures and memories

At first glance, Veles is a street-city, like many smaller towns in Macedonia. But not only that. If you’re a “regular” tourist, you take the main drag, from the clock tower upward; cafés, restaurants, the hospitality “film”—you feel like you’re in Skopje. Scattered around are sculptures by modern authors: Nikola Pijanmanov (“Hamlet”), Ilko Stojanovski (“Blessed”), Goran Stamenkov (“Veles Boatmen”), all made between 2010 and 2020. And Pančo Brašnar is there somewhere—a figure that will keep appearing all day.

In the neglected park by the “Trajče Panov” Local Community (I google: 1921–1942, a partisan commander who fell in battle against the Bulgarian occupiers at just 21) there’s a cacophony of plaques: are they active, do they share premises, or have they just piled up over the years? “Sports Fishing Association ‘Babuna’ Veles”; a huge ugly “Security Agency Panthera” sticker with a lion meant to intimidate. In the background a rustle: is this urban typography or administrative noise?

The first graffiti—and their absence

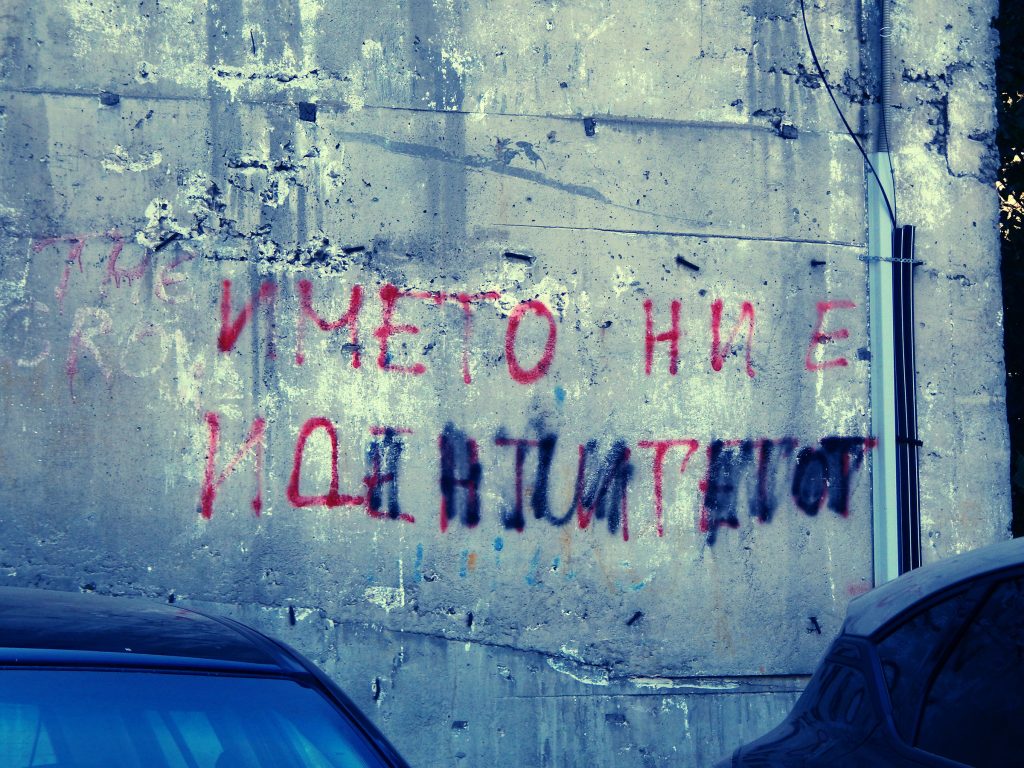

The first graffiti I spot in Veles are political: “They’re gonna (re)open Porcelain Factory, idiots!”—a comment on the endless initiatives to revive the porcelain factory. Urban murals as municipal initiatives exist, but a “spontaneous” graffiti culture—hardly, at least so far. Maybe the walls are freshly repainted; maybe someone diligently scrubs. I expected they’d slip up somewhere. Of what exists, two categories: political slogans (the most common “Our name is our identity”) and pure vandal tags (mostly names).

Urban architecture in the center

I go back (maybe I missed something!) and start over. First “gem”: right in the center, by the roundabout and that four-market mini-mall, a house from 1928. Along the main street a few more older façades; the pinnacle—the “National Museum.” An older man stops me:

“Photograph that building.” — “Yes, I did.” — “It used to be the Assembly.” — “Since when?” — “I don’t know. I’m a ‘45 birth. Before me. I was a footballer. Yugoslavia was a state; we were strong in sports. I played in Skopje, but I screwed up—came back to Veles. Veles is a Jewish town. Everyone knows everyone. And you, what are you?” — “A journalist.” — “Not easy for you either.” Soon the conversation turns dark. The triple murder in Veles that shocked the public. We part.

I watch him drink water at the fountain in front of a Kočo Racin mural; on the neighboring façade—a verse from “White Dawns.” Then a few buildings from the 1930s onward—the “Debar Maalo logic” (the real one, not the newly concocted version). By the “Love Veles” sign stands a cupola that looks like an Astronomical Observatory (which we need like daily bread!), but it’s actually the “Jordan Hadži Konstantinov–Džinot” Theater.

Contemporary traces and the street’s pulse

Exchange offices and shops—with Bitcoin signs. Rare in Skopje; perhaps a shadow from the “website” affair during Trump’s first term—several people from Veles got rich, says city mythology.

I move in a diesel cloud: a constant river of vehicles, buzzing like a hive. Façades stained with exhaust, just like at home! But here’s a difference: in Veles drivers stop the moment you step on a crosswalk. I, a trained Skopje pedestrian, hesitate, wait for a hand to wave me through, raise my hand in thanks and dash across. Surely they know where I’m from.

Pijanmanov’s work looms over the neat Youth Park with a fountain; the line ends at the Church of St. Cyril and Methodius, and a little below toward the “chemistry” high school a group of youngsters enjoy nature and youth. I step into the church; inside, a Glagolitic installation teetering between fantastical and grotesque, kitsch and art. I can’t judge…

Nearby—some Bulgarian center, a Bulgarian flag, a motto “Unity gives strength” (forgive me, I don’t speak Bulgarian!), two statues and an IMRO flag.

The façades along the main road—total Karpoš/Ostrovo vibe. Here I finally run into a series of murals by students (from multiple schools), all in a similar—but excellent!—expressive realism with abstract elements: an eagle, a stag, eyes, waves, birds, horses, a cheetah…

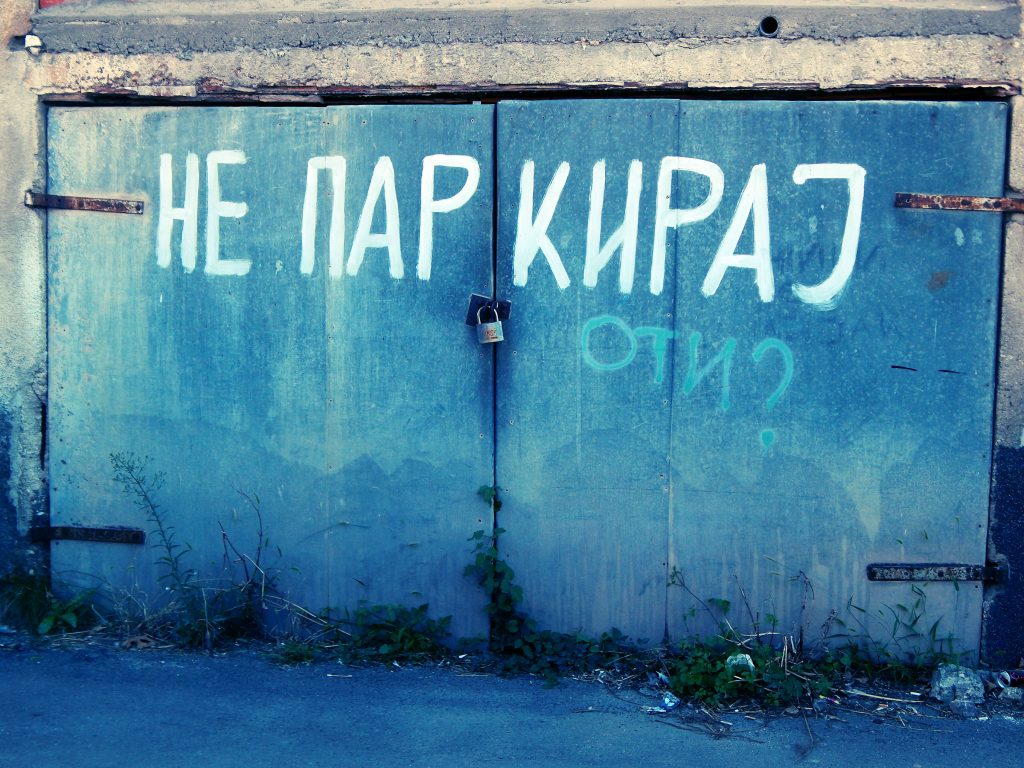

Next to them a little fountain; across the way—the statue of Pančo Brašnar (Google says the first Vice-President of ASNOM and one of the key architects of Macedonian statehood). Opposite—high-rises I’d been eyeing from the center: if there’s no “urban” scene, maybe youth culture gathers under the blocks. I find something, but disappointment—politics again: “Our name is our identity.” And—trash! Finally (ironically!). Where there are blocks, there’s trash. The only creative graffito is covered—by a transformer station. “NO-PARK”—on a sign made me laugh—sounds like an amusement park; actually “No Parking.”

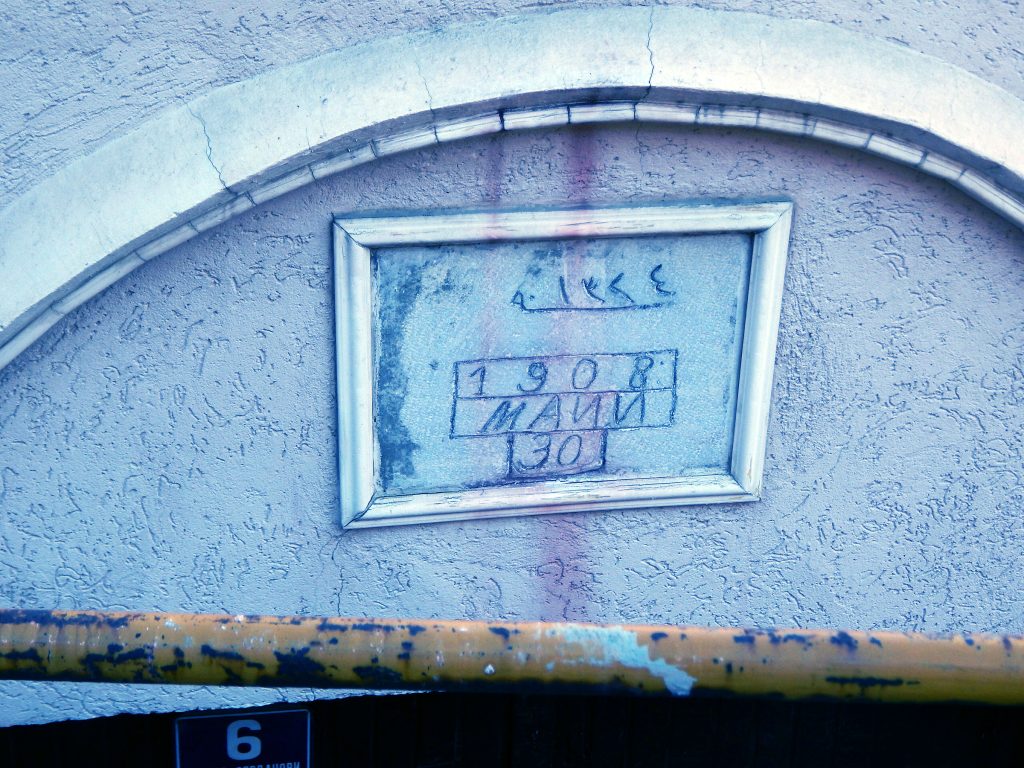

I head back toward the center. A decent commercial mural (Mile, help!)—for a butcher’s! A stencil of Goce Delčev on a street name plate. Two guys eye me—what’s he photographing now? I catch another mural (from a project funded by the Municipality and the Ministry of Culture): “Veles 1908”… Racin again, but at least originally executed.

Back in the center, again

The same plaque cacophony as at the Local Community I see at the side entrance of Europe House Veles: “Socialist Party of Macedonia (municipal),” “Agro Link—Association for Snail Breeding,” “Green Power,” “Association of Disabled Pensioners Veles,” “Municipal Council of Local Communities Titov Veles,” “SSM—Municipal Trade Union of Titov Veles”… Administrative chaos! And the snails?! In the yard—a truly charming little bird mural.

Above them—steep stairs. I enter Steep Veles. On a landing—finally a few (amateur) graffiti: “Anarchy Forever.” Higher up a sign “No littering” and the first stencils. On the transformer—“ZTEФ” with a Chinese character—looks like a deliberate stencil. A bit below—a cacophony of vandal tags. Such scenes in Veles are rare, unlike in Skopje.

Architecture on Veles’ right hill

Surprise of the day: architecture! The main street may be newly composed (except for civic architecture), but the gems live on the hills. Today I walked the right bank (the Clock Tower side). I didn’t see Kočo Racin’s house (a kid urged me to!), but I stuck to the “get lost” method: where the city takes you, that’s your story. (Soon I’ll grasp the absurd of this method—enter character in part two: Nataša A.)

“Upper Neighborhood” above Europe House: the first house—1908; below it more old, decorated houses. A transformer station full of graffiti—sadly, all vandal tags. Higher up, on a garage: “Do not park”—some jokester added “Why?”

Wagons from China

I descend into the city. I hear trains. Wagons labeled: OOCL, China Shipping, COSCO Shipping, Dongfang, Triton, Cronos, Global, tex… These are global container companies. They move along the megaway of Chinese trade—the Belt and Road Initiative. Macedonia sits on the rail corridor tying ports (Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Bar, Durrës) with Central/Eastern Europe. Veles is on Corridor 10—Skopje–Gevgelija–Thessaloniki—a line that reads geopolitics on rails. Most likely the containers arrive by ship to Piraeus, then by rail through Macedonia.

Film intermezzo

The tracks are right by my lodging. I wonder: how will I sleep? I try to remember which film has characters who can’t sleep from trains shaking their hotel. First that comes to mind is Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train—but there the tracks are a poetic thread, not a comic effect. Then Blues Brothers—close, there’s chaos, but not it. Seven? Similar vibe, but not a train-comedy. Planes, Trains and Automobiles? Would make sense, given the title. And finally—lightbulb: My Cousin Vinny! The legendary 5 a.m. train that’s practically a main character. That’s how I feel in Veles—like I’m inside a film scene.

I go down to take photos. Bell rings, the barrier drops. I ponder crossing; the guard tells me, “It’s ok. Not right.” in English. With camera on my neck and backpack on my shoulder I probably look like a foreigner. The barrier goes up; the train doesn’t come. By the tracks—an old wooden hut, like in a film. A bit up—peeled-off shop window of the former “Lala” pastry shop: “pancakes, sweets, cakes, lemonade, boza, coffee.” Above that—kebab place “Don Toni.” Of all these—only the barbershop “Tame” works. The thesis my father told me as a kid holds: “All businesses can fail; only barbers can’t.” Human vanity is the most persistent valuation system.

Further up—the tavern “Bojem” (I’ll dine there later with my laptop on the table—to the waiters’ bemusement!), before the roundabout with the horse statue—a dedication to Veles’ Ilinden fighters.

Steep Veles

Veles is as steep as my hometown, Sarajevo. Narrow streets, old gates, Ottoman-era houses, fountains, water flowing straight down the road. I descend and before the main road I run into a graffito that looks like ganja (Towlie from South Park), and that’s how I jot it in my notes (which are actually a pencil), and a Joker with a long tongue. Along the way—murals sponsored by the Ministry of Culture, SCM and the Municipality of Veles (saw the same in the center): “Western,” Prince Marko, Racin’s “The Diggers,” and a verse by Racin.

Yes, Racin is a pillar. But (no offense, people of Veles!) the city is oversaturated with him: murals, quotes, street names. Veles is not only Kočo Racin. Veles is also Pančo Brašnarov (Google says: 1883–1951, revolutionary, fighter for social and national rights, the first Vice-President of ASNOM); Vasil Glavinov (the first socialist in Macedonia); Ilija Glavev (author of the first constitution of the Social Democratic Party of MK), and many others. Veles is the heart of socialism in Macedonia. Veles is the old houses on the hills. That’s how it should promote itself.

The upper neighborhoods

Finally the clock tower (even though I told myself I wouldn’t be a tourist, I’d get lost in alleys—but it’s on my way). On one side a gate; on the other—houses and a little dog that greets me by barking. The house in front of the tower—fully “restored” with “authentic” ornaments and PVC doors!? The old gates—as a counterpoint to Skopje’s omnipresent PVC—call me. I start documenting them, like they’ve stepped out of Macedonian folk tales. Some are so buried in asphalt heaped over old roads they look like doors for dwarfgiants. And in fact they were for Veles’ Giants!

(Gallery follows—click to enlarge!)

Doors and windows on Veles’ right hill

A mural of Kočo Racin (again!), Toše Proeski and Mother Teresa (via Midjourney). I’m not even aware I’m near Kočo Racin’s house. Downhill—Soleno Češmiče (a historic salty spring that for centuries was the social center of the lower town): a Mickey Mouse graffito turned with his back (why? out of spite!), a few benches, a shelter, a table with the Macedonian flag—a gathering spot for the neighborhood. Houses cracked, on the verge of collapse—“for sale.” Crafts extinct; a tailor here and there; the goldsmith shut the shutters long ago.

In the “upper neighborhood” I hit a house that’s collapsing, literally sprawled across the street; behind it a big dog barks. I retreat 2–3 houses. By the house where the Krapčevs were killed, a man greets me. “Is there a dog up there, is it tied?” I ask. “I don’t know,” he replies. We start chatting: in his house they found a hideout and guns; the upper neighborhoods are dead, depopulated. “Did you photograph the ruined one? Send the photos to the Municipality, it’s a shame.” He wants to sell his house and move to the Center. I tell him: it’s a mistake to develop only the center—foreigners don’t come for cafés; they want authentic culture, old buildings and neighborhoods. These steep streets are perfect for that. (Instead of Siena—discover Veles! I coin a slogan to myself.) Veles has things to show— we only need to believe in it.

Lower down I document a lock, a window, a handle… The house of Ilija Glavev (a lawyer and politician who in 1910 wrote the first constitution of the Macedonian Social Democratic Party); Pančo Brašnarov (the first Vice-President of ASNOM) winks at me from history again. I’m not showing photos of the houses of these and other greats here—you’ll find those elsewhere; here I’m sharing the hidden, forgotten alleys.

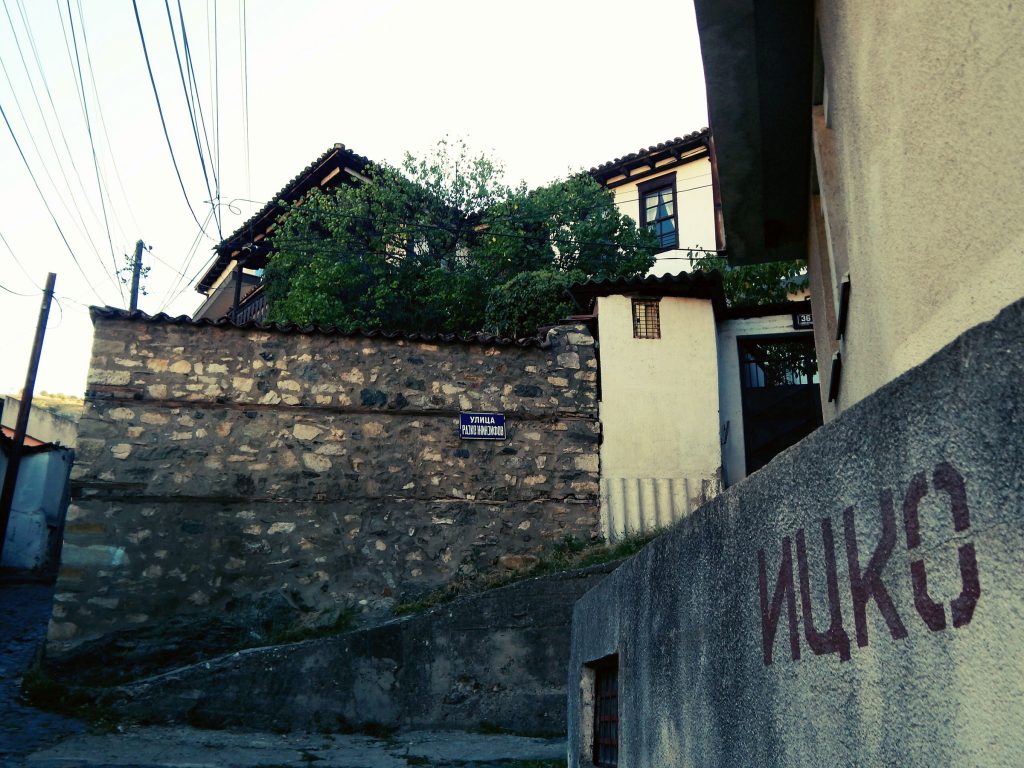

I almost missed Vasil Glavinov’s house (in 1909 he laid the foundations of the workers’ movement in Macedonia). While photographing a stencil of “Icko,” a man watches me from a terrace and shouts, “The plaque is on the other side.”

And indeed, on the other side it reads: “In this house lived Vasil Glavinov, the first propagator of socialism in Macedonia.” I had unknowingly photographed his house, just as I’ll later realize I had also photographed Kočo Racin’s—more on that in the second part! For now: finally two graffiti that smell of Skopje—but amateur.

“Kočo Racin is mad at me!”—an inner monologue as I stroll along the streets of the same name. At the bottom a “Železara” (Ironworks) sign with an excellent font greets me—I instantly think to send it to Nebojša Gelevski—Bane and his Lokomotiva, as a typographic trophy.

Evening, laptop in a restaurant

At “Bojem” restaurant, solid food. The waiters are kind even if they’re puzzled by my request for a table with an outlet. I pull out the laptop, the day’s notes, skim the photos and write. Next to me a classic conversation: “they released money,” says a 100+ kilo living Balkan specimen. I hear this phrase more and more in eateries, accompanied by turbo-folk business aesthetics. Worlds hovering like smog in every street-city in Macedonia.

I stumble upon a photo of the sign toward Racin’s house. The legendary Macedonian poet seems a little angry on the sign. Or angry at me? Forgive me, I didn’t see your house! Understand, I’m not here as a tourist, I’m here as an urban archaeologist. But even there I fail. I know nothing of the city, of architecture. All I have is a camera and words.

Epilogue, or “What I learned about Veles today”?

On day one I learned: Veles is not just the main street with cafés, casinos and eateries. It is a city of hills. While searching for graffiti, I found houses from 1908, porches, doors for dwarfgiants (small doors for big people), plaques that speak louder than their institutions, rails that carry goods from Asia to Europe, and a concerned neighborhood voice that told me: “Send the photos to the Municipality. It’s a shame.” I don’t think Veles has anything to be ashamed of—on the contrary, it should be proud! Veles is the heart of socialism in Macedonia, and its hills are the skeleton that holds the history of this small place. You just have to stop, look up—and the city will speak to you itself.

P.S. Dwarfgiant is a neologism coined by Nikola Gelevski for the book Džindžudže in the Land of Poppies; I felt it fit well as a title motif for this text.

Read the second part of the text.

This article was originally published in Macedonian.