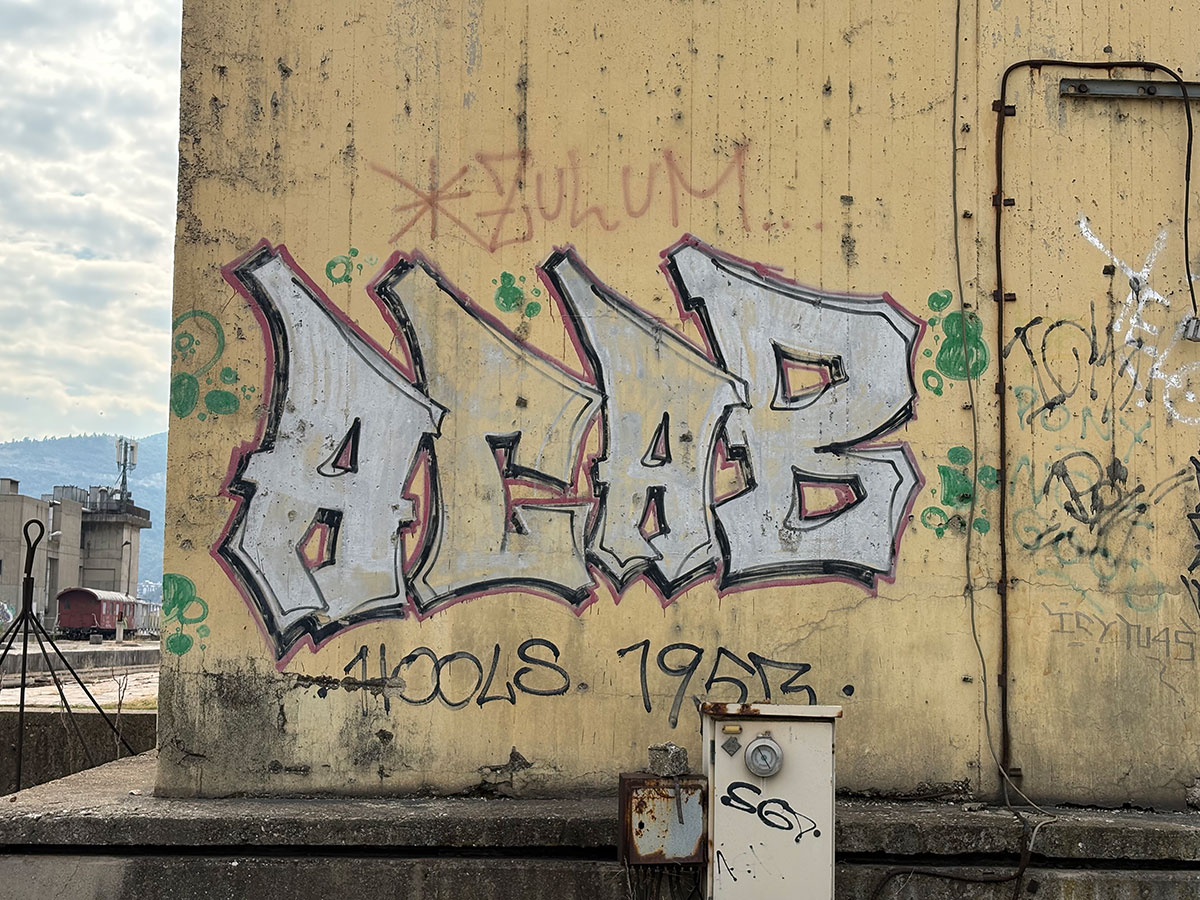

Skopje’s railway station. Today, the platforms and the old carriages stand like relics of a forgotten utopia, while their walls—covered in graffiti—tell a different story: of rebellion, memory, and endurance. Up here, above the city, a strange silence reigns—not the calm, meditative kind, but a cracked, depressive one, like the pause between two trains that never arrived.

The rusted wagons and the living colors of the graffiti merge into a portrait of urban decay and resilience, where every tag is a small scream against inertia. The concrete is tired, time has stopped on the clocks, but the spray paint is fresh—and that creates an odd blend of former progress and today’s improvisation. Here, where one was once supposed to step into Skopje’s future, we step into something else: a museum of abandoned visions and the stubborn traces of people who refuse to accept this as the city’s final version.

About the (New) Railway Station and Writing

I photographed the graffiti up by the platforms of the New Railway Station maybe two months ago, and ever since, the thought has been following me: “I should write a text about this.” That sentence—“I should write a text”—often means, for me, that there’s something deeper than simple documentation.

Don’t be mad at me, especially you, Bane (Koma)—I’m going to use the (technically incorrect, but living) expression “the New Railway Station.” That’s how I grew up with it, that’s how it’s stamped into my brain, and dropping the “New” sounds like someone trying to forcibly change your nickname in your fourth decade of life. And, let’s be honest, I won’t be consistent anyway—I’m writing in stream of consciousness, not in a railway traffic rulebook.

As I said, I tried a few times to start this text, and every time I ended up in a new rabbit hole: researching the station, the trains that stand here like a permanent exhibition, the history, the architects, Kenzo Tange, the plans, the utopias… and I still couldn’t get to the essence.

Why? Why does the text slip away every time I try to catch it? Because one very simple question keeps bothering me: “What new can I say without repeating myself?” I’ve already written “Concrete Gallery: Graffiti under the New Railway Station” and “FLIM, White Night and the Graffiti under the Railway Station: Part Two.” On Arno.mk and in Graffiti.mk I’ve published more than 250 photos of graffiti on, under, and around this station. I’ve already told stories about my weekly little pilgrimages from Debar Maalo to Pop Top in the Skopjanka mall, passing through the station, with all the references to the breakup of Yugoslavia, the transition, the decay of the spaces around it and beyond.

What can I add without it becoming rinse and repeat? All the architectural and journalistic texts, with technical data and symbolism—how this station is the core of Kenzo Tange’s failed dream, how the city became its own monster, how the trash around the station mirrors the “shakiness” of everything around us—this has already been said. My texts and other people’s texts pulse on that same nerve.

And yet, something remains unwritten. Some “wire” I can feel. Maybe it’s that one story that will tie all the previous ones together—if not for others, then at least for me, as the author of these “railway episodes.”

2025, Skopje

I dropped the kid off at school. “The kid” hasn’t been a kid for a long time, but I still call him that—out of spite toward time. There are no buses from Novo Lisice (damn place) to Kisela Voda—except one cursed number 13 that’s always packed like a can of sardines—and down there, in Kisela Voda, acid rain falls from tons of sulfur, nitrogen, and God knows what else that Usje pumps out every damn second of our damn lives. (Sorry for the swearing. But I’m just speaking the way I hear the world.) So we play this morning routine—at 7:00, through disgusting city traffic, to reach the grinder for young brains. I still have two hours before I start work (designer, my mother gave birth to me, what can I do). And for days now, I can’t get one thought out of my head: “I need to go up to the platforms of the New Railway Station and photograph the graffiti.”

I haven’t been up there in years. Ten? Twenty? Forty? I’m no longer sure. And that very “confrontation” with the upper part of the station—with the platforms, with what has happened to “my” Railway Station—blocks me.

I realize that all my circling around the station, photographing the graffiti underneath it, off to Prolet, the Public Health Center, toward the Vardar and the river quay—has actually been avoidance. Avoidance of the core of my problem. But something—some devil—pulls me exactly up there. And I decide to find out what.

In my ecological groups (note to self: insert an SEO link to the groups and texts), I’ve written several times about the station’s neglect—about the decay, the dust, the broken parts, the lack of maintenance… and I did that even before it became “cool.” I’m grateful for every journalist’s report by people who love this station in a similar way—at least I’m not alone in this madness.

The trash in the area hits me first: in the eyes, in the nose, in my sense of order, in my responsibility toward the community. All those “senses” suffer there, synchronized. I photograph a tag by Kuchen, a foreign writer known for huge signatures in unusual places (and often for disrespecting them). It greets me right next to a poster of some “turbo-folk singer.” Wonderful Skopje in one frame: a global graffiti tourist and local turbo aesthetics side by side.

I notice the traffic cameras at the intersection in front of the station and I understand their purpose—traffic safety. Of course. But in the process, aesthetics and architectural principles are thrown out the window—the structure is clumsy and visually slices through the view of the station, like a parasitic add-on to something that used to be beautiful.

And behind that, glued onto the station itself—jungle: billboards and ads. And, as the cherry on top: a betting shop right at the entrance. A Balkan rhapsody in a few visual layers.

Intermezzo: The “(K)Urbanists” once again prove the city has long been sold off to whoever has money. Cultural heritage doesn’t matter, aesthetics don’t matter, not even the first impression foreigners take when they step off the train. What matters is advertising, buying a ticket, selling a dream of wealth to the poor.

Here’s a free slogan: “Welcome to a city fed by the Kurbanists!” or “What the earthquake didn’t destroy, the kurbanists fed.” (Yes, I know—it’s rough. But what they’re doing to the city is rough too.)

And to be clear: I don’t mean the urban planners who truly built and cared for Skopje, but the others—the ones approving plans for the New Skopje, the ones we all know. Anyway.

On a small transformer station I’m greeted by an Andre the Giant sticker and an EG stencil. One is a symbol of global urban culture; the other belongs to one of the rare local graffiti authors who sign with a monogram that’s more than a signature—it’s a symbol. A small sign that urban culture, like a nerve, still keeps the dream of a modern Skopje pulsing beneath this corrupt crust.

I photograph the station murals—a girl, bicycles, unicycles—and head toward the main entrance, avoiding the taxi guys by the side entrance and the parking lot. The moment they see someone with a camera, they think: foreigner—and instantly: “next victim” to skin for personal profit, not caring what image they project of the city globally, or how many customers they’ll lose long-term. Microeconomics of the short term.

Inside, the New Railway Station looks like someone opened it yesterday and forgot it until the day after tomorrow. Nonfunctional doors, peeling rubber walkways, pigeons nesting and leaving their own “bio-graffiti” on the walls, ceilings that expose the station’s belly—like a creepy grotesque counterpoint to Borko Lazeski’s murals in the Old Railway Station. The escalator (of course) hasn’t worked in ages (note to self: mention it in the other part too).

In the waiting hall there’s more dust than people; on a chair, a forgotten dirty shirt left by some drifter. Through the windows—covered with more spiderwebs than Dracula’s castle—you can see Blvd. ASNOM. From the old signs only “…rnational Informations” remains, like an ironic caption for something that no longer informs anyone.

Finally I step out onto the platform. The city reveals itself beneath me as if I’m seeing it for the first time—though 38 years have passed. It doesn’t look that bad, I think, if you overlay the view with the idea of an old photograph.

To the left is the heating plant chimney; in front of me the boulevard—Ostrovo and Michurin on both sides, an interlude before Aerodrom (damn place). Behind me—Prolet, Jumbo, Madžir Maalo without the old houses, ZOIL; to the right East Gate. That’s the circle I’m located in: a private, psychogeographic map of Skopje in a few coordinates.

1987, Sarajevo–Skopje

It was 1987 and I lived in Sarajevo. (Those who know my travelogues can skip this; the same trauma tends to drag us back to the same place like a sadistic director.)

I was standing at the window in the living room of my grandfather’s apartment in the Old Town. A few years earlier we had left the family house above Mejtaš, which my father lost in a court dispute with his second wife.

We lived not far from the Cathedral and the Music Academy, on the hill above Baščaršija. Winter covered the valley with thick fog like a lid on a pot, but that day another scene opened in front of me: the silhouette of a small woman, scarf over her nose, bag in hand, pushing through the snow—clumsy but determined—where on uncleared patches it reached her knees. That’s how I met my mother.

Until then she was something between a myth and a shadow: a figure from early childhood, someone who sent packages for New Year’s and birthdays but wasn’t physically present. My three-year-old self had been left without a mother—she had been pushed out of his life. But what does a child know? For him it was the same as if she had died. Ten years later, his father would disappear by his own choice. So that child became an orphan twice in his life—while both parents were still alive. Human psychology is strange.

We get off the tram in front of the Sarajevo railway station. A huge semicircular building with two massive clock towers. Later it will become clear to me that I will recognize those towers in the New Railway Station in Skopje. A socialist-modernist classic, completed in 1953. Inside—a large hall with terrazzo floors, high ceilings, several ticket counters. My mother buys two tickets to Skopje. Through cigarette smoke, the smell of coffee from the buffet, people with big bags and cardboard boxes tied with rope, the loudspeaker cuts through: our train will arrive soon.

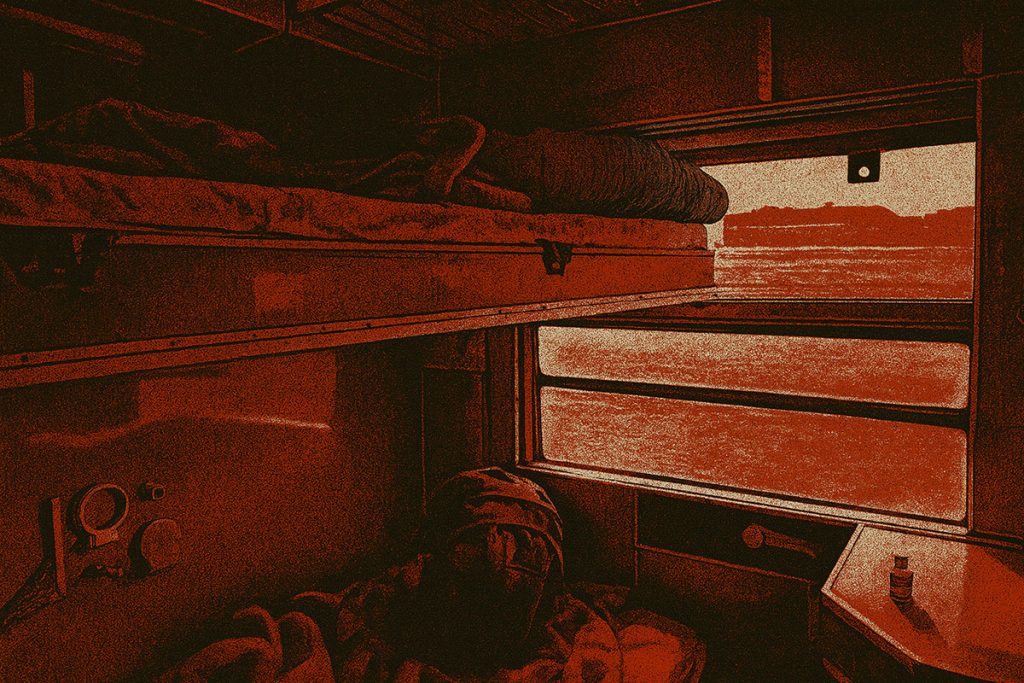

We board a Yugoslav Railways carriage. To make it more comfortable for me, my mother got a sleeper car—and to me that was pure magic. We traveled a long time, maybe fourteen hours. We solved crosswords, talked about everything and nothing. That’s how, at ten years old, I “met” my own mother. I don’t remember the stops and the exact route in detail, but the feeling is clear: the sleeper car, enclosed and warm, that specific train smell, the passage between cars like a doorway into a parallel world, the tiny toilet you can barely turn around in, and the hole through which you can see the tracks. The windows were fogged; outside, the world dissolved into snow and darkness.

I lay on the upper bunk and listened to the rhythm of the wheels, that monotonous, hypnotic sound that rocks you between waking and sleep, where time isn’t measured by a clock but by unconfirmed stations you remember as shadows. I think that’s when I fell in love with trains—and they remained my favorite way to travel, not because of speed, but because of the temporary vacuum they create, and the rhythm that fills timelessness.

The train surely stopped in Zenica, Doboj, maybe Belgrade or Niš (now I play the same game as the main character in the film Lion, searching on Google Maps to reconstruct the route of the train that carried him far from home). In my memory, though, those names are only flashes, like faded letters on a signboard blinking in the night. I remember short bursts of light, vague voices from platforms, footsteps in the corridor, the sound of a door opening and closing. Outside we were probably passing mountains, frozen rivers, landscapes I saw then with a child’s eyes, and today they feel like scenes from a film I’ve forgotten—yet the body still remembers.

In the morning, grayish light. I look through the window—and the city is beneath us. I can’t understand why. I see the clocks on the concrete towers and they remind me of Sarajevo’s station. When we step onto the platform in Skopje, everything seems new, familiar, and at the same time slightly foreign. Like I had arrived in a parallel version of something that would soon become “home.” (Of course, I didn’t know that yet.) The station hovers above the street, firmly anchored on massive concrete pillars. To go down we use the escalator—another little miracle of modern Skopje. We exit and step into the city’s bustle.

That’s where my first “episode” with the New Railway Station ends, because it stays behind us—in the fog of Ostrovo, Michurin, and Aerodrom—while we head toward other horizons of the city on my mother’s side, a city I still had to discover. And that’s why this present story about the New Railway Station isn’t only about today’s condition—about decay, about new visions—but above all about the graffiti. Because they, too, are the city’s pulse: urban life between pollution, traffic, horns, and drunks. So we can remember them before someone decides they should be erased.

Back to 2025. Back to Skopje

I’m back on the platforms. The first thing you feel up here is “space”—emptiness. The huge open volume in front of your eyes. The towers by the tracks rise like border posts, signposts, and at the same time guards of a different time slipping into the past. (Not by accident—the clocks on them really have stopped.) Each tower is covered with large graffiti pieces.

“Skopje, are you still alive?”

„Скопје, живееш ли?

On one side, BORIS dominates—an enormous tag in multiple places, as if he has written his ownership over the space. PONY, several anti-graffiti messages, PSG and others—impossible to read—GTA, MFG-PR, and a question-graffiti that hits you directly: “Skopje, are you still alive?”

Across planks set up like improvised stair-bridges, I cross the gap where there were tracks (or maybe there never were?). Behind the concrete towers—an excellent rebus-graffiti reading “Smut Kriminal.”

Only while writing this do I understand how well it’s conceived: it’s a wordplay by Smut (Smut Letters, a guy with a strong sense of typography) and an association with Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal” (also hinting at the fact that a graffiti writer, in the eyes of the law, is a criminal).

Further on—an industrial landscape: pipes, installations, removed (or never installed?) rails ending in nothing, like cut-off sentences. Glass shards, metal pieces, pipes that spill water onto the platform.

Another small revelation: I understand why water constantly drips from the station’s ceiling onto the pavement and street below. Everything is connected—literally.

Between the towers there are doors. Some lead to stairs, others to elevators I doubt are functional. Blue metal doors covered in rust and tags; a panel with broken buttons and the old iconic label RK, “Rade Končar.”

Wagons as a Permanent Exhibit

On the side tracks a wagon is anchored, fully “dressed” in a large fluorescent piece by IBES NICE, with a humorous and slightly ominous message “Greska izvini,” a crossed-out “I LOVE,” then SLAY, IVS, and a bunch of other tags, including Hello Kitty—as if someone planted a children’s icon into this rust parade.

I research online: it’s a service railway wagon “sleeping-kitchen” of class Uk-zz, registration number 40 65 9050 028-5. Today, a service wagon adapted from a former four-axle passenger coach. About 20 tons, capable of moving up to 60 km/h.

On the other side—ROLF 2022, Skimad, TWBZ 2022, Yo:Samu Leny, ROLF TWB, a tag by CHRIS, a writer from the third generation of local graffiti artists active over the past decade.

A few railway employees step out of the wagon. One of them asks me: “Will there be anything new?” At first I don’t understand. Then it hits me—he probably thinks I’ve been sent by the railway administration to document the condition. I explain that I’m a journalist interested in graffiti and old buildings and vehicles.

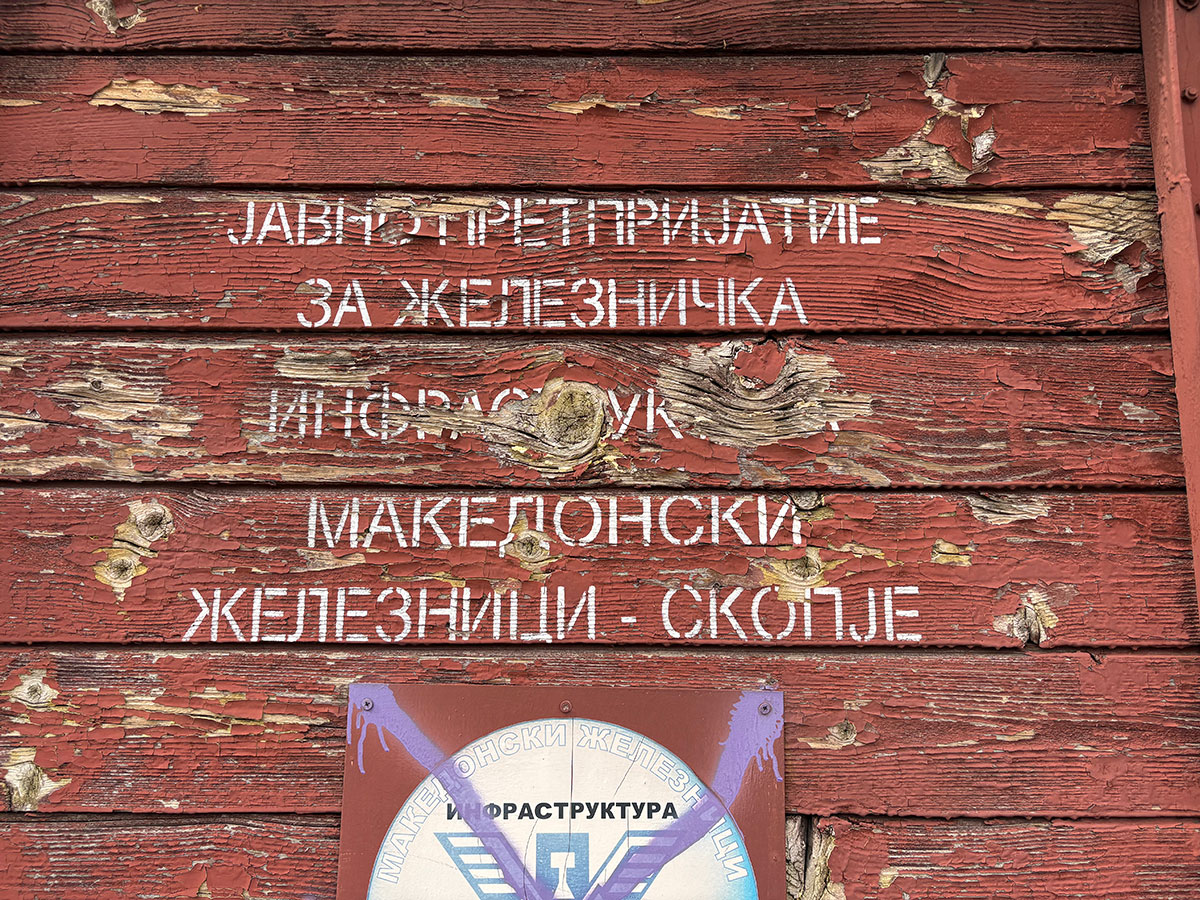

He tells me the wagon is from 1913 (maybe he means the other one further away). He adds a morbid detail: that during WWII the occupiers used these wagons to transport Jews to the camps. He relaxes a bit and starts pouring out his soul: “Everything here is falling apart. Who am I supposed to work with? They brought me a shoemaker who has no clue about railways.”

He talks about how in the past everything was different, when the railway worked “as it should.” I confirm it. He doesn’t believe me—“how would you younger ones know?” I tell him I’m almost fifty. He’s surprised; I look younger to him. He leaves; I continue photographing.

I read online about the wagons below: wagons marked “Uk-zz 40 65 9050 028-5” are listed as “service wagons”—not freight, not passenger, but special-purpose. Wooden freight wagons with classic “X” braces, wooden cladding, hand ladders, later adapted for infrastructure use—storage, offices, guard duty, then “sleeping-kitchens” for crews. The design is typical of early 20th century to the 1940s.

What do we know as a certain historical fact? The Jews of Macedonia were deported in March 1943 from the “Monopol” camp in Skopje to Treblinka, in three transports using freight/cattle wagons. In the Holocaust Museum, standing wooden wagons symbolize those journeys. The wagon I see here is typologically similar, but many wagons of that type were sold, modified, and renumbered after the war. So to know whether this exact wagon has a “genealogy” linked to those transports, an archival file would be needed—one I, naturally, do not have. And maybe no one has anymore.

Towers. Clocks. Skopje

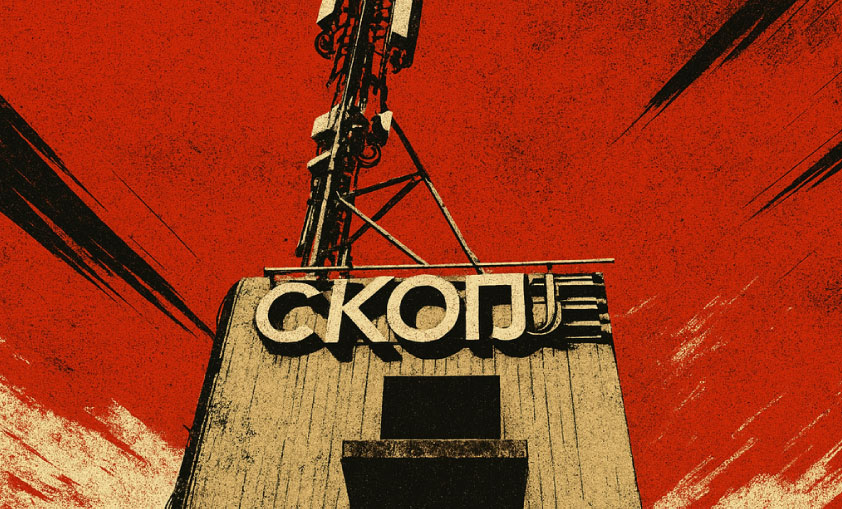

Behind the wagons, the towers open up in full scale. On them, the big 1980s inscription “SKOPJE” and the stopped clocks. All past and future passengers enter a retro adventure: “Welcome to the city where even time has stopped!”

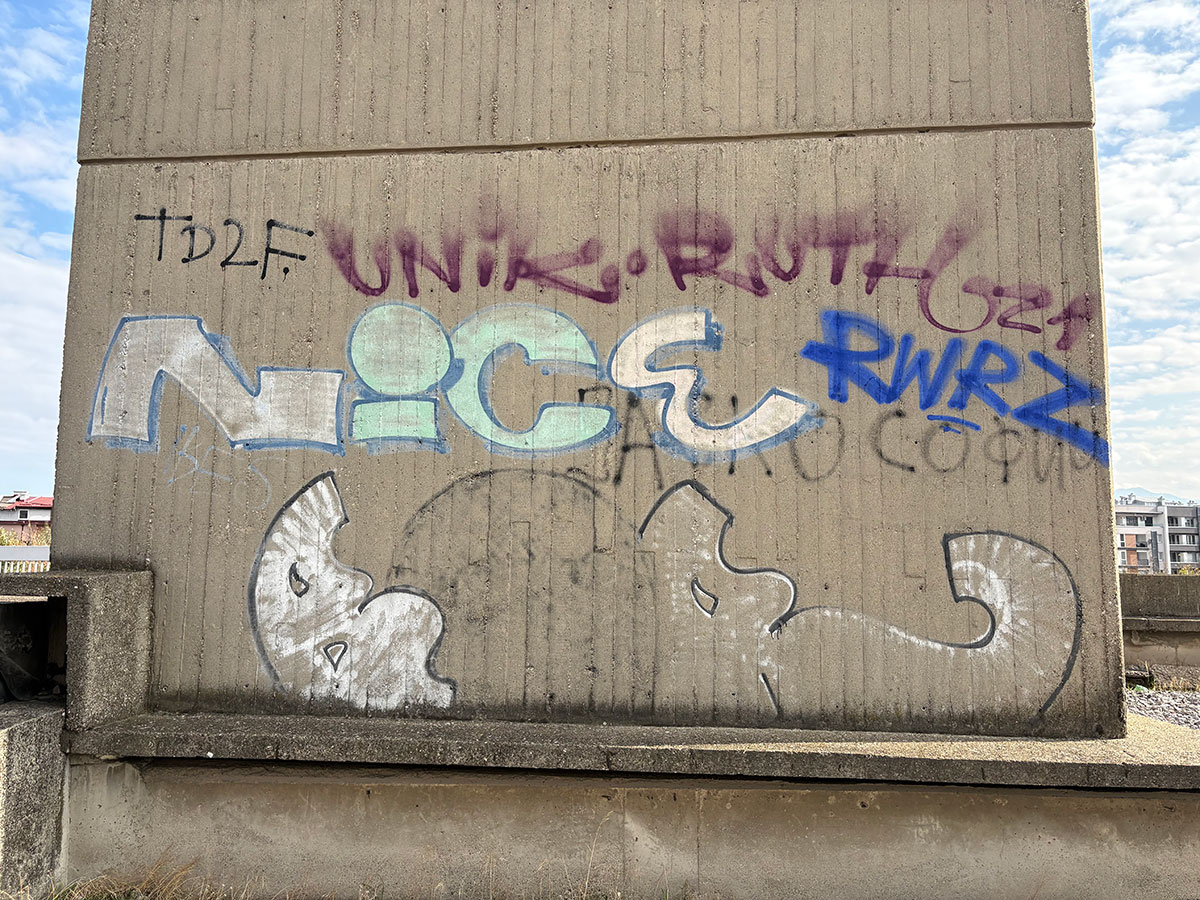

Each tower, on all four sides, is covered with local and foreign pieces. Here are TD2F, with the heating plant and the new Skopje rising over Keramidnica’s ruins behind it. IBOU DEX1, with the Neocom building behind. An unfortunate ACAB under the SKOPJE sign, next to it YELO, SODA, an unrecognized piece accompanied by SKOPJE 2025 and others.

The signs are rusted, barely readable (Stop? Something else?), and nearby there’s a track maintenance vehicle. On the other side, big pieces: FATZOO, JEANZ STLER, JASON, again BORIS (with a mini-landfill in the frame), IBES, TFC, F.C.K., and various tags over an old-fashioned phone.

ROBEL. Graffiti.

Railway fanatics tell me: model TMD–ROBEL 54-15-2. Attached to it is ROBEL 046—a closed service wagon of JSC MŽSM, intended for tools, equipment, materials for interventions.

Two great pieces are on it. The marking is clearly visible, and at first I think: RWRZ (a writer present in multiple places on and around the station) showed respect and spared the marking. Later I realize—no, the employees erased that area; they left the rest under graffiti. The other side is fully covered by MORE.

Platforms. Wagons. Locomotive.

I go back toward the platforms, slightly hurried. Quickly I photograph the kiosks that, by all appearances, “worked a hundred years ago,” more like film scenery than an actual remnant of the past.

I want to “catch the train.” Not to travel with it somewhere far, but to catch it visually, to document the pieces on its body. I often hear local writers complain that not enough trains get painted here—this one is a counterexample. It’s fully covered with big, serious pieces.

Yugoslav steel second-class compartment coaches, rough and heavy, produced from the 1960s in “GOŠA” Smederevska Palanka, traveled across Yugoslavia, and since the 1990s—after being purchased by Macedonian Railways—have “settled” here. By today’s standards, comfort is modest. From outside you see compartments, small windows, no AC. I don’t enter, but I can feel the smell of metal and dust.

Under the graffiti by HFAT, IRIS, TUKES, STZE, HFAT, ASHE, ZORK, over WOO HOO, IBES and others, the technical poetry hides: 50 65 20-10 002-1, 50 65 20-10 000-5 and similar markings. On one plate it says the wagons are serviced once a month.

The powerful electric locomotive pulling this composition is MŽ 441-044, from 1970, produced by “Rade Končar,” based on the Swedish SJ Rb. Power 3.8 MW, max speed 120 km/h. A universal locomotive of Macedonian Railways—today wearing a patina and graffiti of half a century of Balkan history. The whole train has more than 50 years of service behind it.

The train still hasn’t departed, and my mission is slowly coming to an end.

The Towers on the Other Side of the Platforms

I head to the towers on the other side of the platforms. Again I’m greeted by huge pieces, but now with even clearer signs of decay: the SKOPJE letters cracked and missing. Sometimes it’s KOP*, sometimes SK**JE, or some other combination.

The clocks are stopped again. And inside me, it’s as if everything calms down—only the graffiti remains, against the backdrop of the city I first saw from above: wide and beautiful.

Here are HYPE with IBES, MORE and RWRZ with SOT, a colorful KMG WDS, and a black-and-white bubble masterpiece by WOO HOO (KPC 143). At the end—WDS and UGE, NICE, ENSOR and IRASO on separate towers, as well as our PACK and HROM, who painted some pieces together.

And somewhere here my photographic mission ends. As always, the text and some of the photos will end up on Arno.mk. Some frames will remain in my archives—maybe someday their time will come too.

I climb down from the New Railway Station (sorry, Bane!) feeling both full and empty. The day moves on, I return to work obligations in the machine that grinds me. And of course, I don’t write the text immediately.

Almost two months will pass before I sit down and pour this out. Did I say what I wanted? Maybe. I don’t know. Maybe, in the end, the journey matters more than the destination.

This article was originally published in Macedonian