Houston, this is Skopje…

In September 1970, at the height of the Space Age and during the Cold War, the original command module of Apollo 10—the mission that paved the way for the first Moon landing—was exhibited in Skopje, a socialist city still rebuilding itself after the devastating 1963 earthquake.

This article presents an English translation of an original newspaper report published in Večer (No. 2269, September 16, 1970), offering international readers direct insight into how this extraordinary event was experienced and documented at the time.

THE ORIGINAL APOLLO 10 COMMAND MODULE IN SKOPJE

HOUSTON, THIS IS SKOPJE…

- GREAT INTEREST IN THIS SPACE “PASSENGER”

- 1,000 VISITORS IN ONE HOUR

“…This is Houston. This is Houston… Stafford, can you hear us…”

“OK. This is Stafford. Everything is ready for splashdown. We are all feeling well, eagerly awaiting the moment we touch the waves of the Pacific…”

The voices of the three Apollo 10 astronauts—Thomas Stafford, Eugene Cernan, and John Young, the three heroes of space—resounded once again. In 1969, they became the first people from Earth to orbit the Moon, bringing the lunar module to within just 12 nautical miles of Earth’s satellite. Yesterday and today, they are figuratively “at the disposal” of the citizens of Skopje.

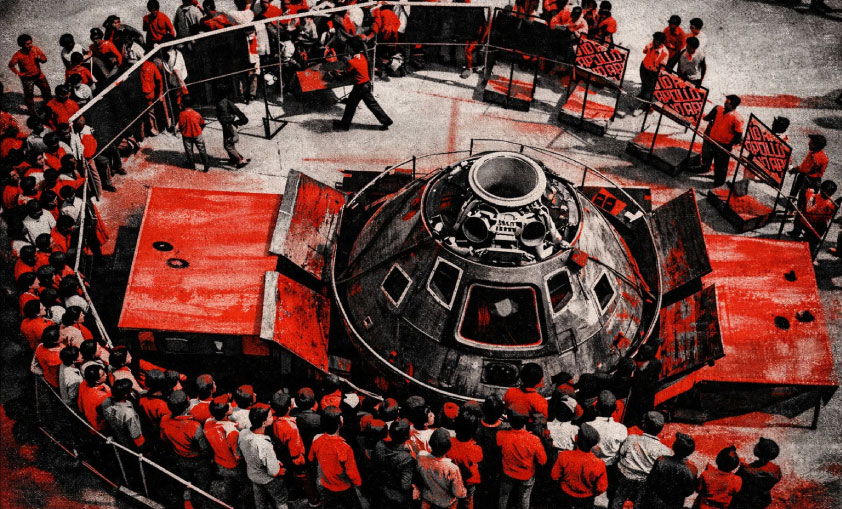

After a several-month tour of Europe, the Apollo 10 command module arrived in Skopje and is now exhibited at Freedom Square, in front of the Builders’ Hall.

GREAT INTEREST

The interest shown by the people of Skopje in this unusual “guest” of our city is more than remarkable. An endless line of curious visitors waits their turn to see the original command module. At the exit, a counter recorded 968 visitors within the first hour after the traveling exhibition opened.

A loudspeaker repeatedly recounts the “history” of the command module and issues a warning: “Visitors are kindly requested not to linger too long and not to touch the capsule with their hands…”

While visitors wait in line, the organizers make an effort—through various brochures—to acquaint them with the details of Apollo 10, and at the end, each visitor is presented with a commemorative badge.

Mr. Fentress Gardner, director of this traveling exhibition organized by the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, spends the entire day next to the command module. We asked him to tell us something about the Apollo 10 tour.

— Since the beginning of April this year until today, we have visited several European countries. We started in Budapest, then continued through Plzeň, Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Vienna, Ljubljana, and Belgrade, and now we are here in Skopje. We will remain here until September 17, after which we will depart for Bulgaria. So far, our largest attendance was in Poland—120,000 visitors over nine days.

— What is missing from the command module, and why is touching it forbidden?

— Only the hatch through which the astronauts enter is missing. We replaced it with transparent glass to allow visitors a better view of the interior of the capsule, since the windows on the original hatch are too small.

— As for why touching the capsule is not allowed, the reason is simple—Mr. Gardner explains, inviting us to try it ourselves. We touch the lower part of the capsule, and our hands are left blackened. The lower section was burned by extreme temperatures, and what was once solid material has become charred.

SKEPTICAL SKOPJE RESIDENTS

We also joined the line of visitors. We wanted to listen in, to observe the reactions of the crowd. On the capsule, which weighs 5.5 tons, it is written that it is original—and this is constantly repeated by the announcer over the public address system. Nevertheless, there are quite a few visitors who shake their heads in disbelief.

— It would be madness—Mr. Gardner explains—if we were to make a replica. It would cost us as much as the original. And this skepticism is not unique to Skopje; it happens everywhere. But once visitors see the burned capsule, they immediately change their minds.

• A ten-year-old child asks to enter the capsule and wonders whether the three figures inside, dressed in astronaut suits, are the real astronauts. Meanwhile, one student is pleased to have collected several Apollo 10 emblem badges, while another, an elderly man, asks whether a model of the lunar module can be purchased…

• Another visitor—most likely having just arrived from the Tikveš Grape Harvest—carrying a full set of alcoholic beverages in his hands, tries to convince Mr. Gardner that what he is holding is a “Macedonian Apollo” and that “with it one could travel farther than the Moon…”

T. Naumchevski

At the time of the exhibition, Apollo 11 had already become history. Humanity had walked on the Moon, and Apollo 10 was widely recognized as the critical rehearsal mission that made that achievement possible.

The presence of the Apollo 10 command module in Skopje was therefore not a marginal event, nor a symbolic replica—it was an encounter with the actual spacecraft that had orbited the Moon.

In the context of socialist Yugoslavia, this exhibition reflected a broader moment of openness, international exchange, and scientific optimism. Skopje, rebuilt through global solidarity, briefly stood at the intersection of post-earthquake reconstruction, socialist modernity, and space exploration.

Why This Translation Matters Today

This event is almost entirely absent from digital memory in North Macedonia and the wider region. There is no publicly accessible, searchable digital archive where such material can be easily found. Without physical access to newspaper archives, the story of Apollo 10 in Skopje would remain effectively invisible.

Publishing this translation is therefore not only about space history—it is about archival access, collective memory, and the responsibility to preserve modern history before it disappears.

Conclusion

Apollo 10 in Skopje was not merely a technical exhibition. It was a moment when a post-earthquake, socialist city encountered the Space Age firsthand, through an original artifact that had traveled beyond Earth.

That this moment nearly vanished from public consciousness serves as a reminder:

history survives only when it remains accessible.

Source

- Večer, Year VIII, No. 2269, September 16, 1970, Skopje

- City of Skopje Archive (photographic material)

- Retro News: September 16, 1970 – When Apollo 10 Landed in Skopje, a City Torn Between Reconstruction and Forgetting (in Macedonian)

This article was originally published in Macedonian in 2 parts.